In 1896, the year Frank Palmer Smith was born, his parents Jacob Adam and Mary Ellen 'Nell' Smith (nee Mincham) bought a block of land along the Sturt River in Coromandel Valley where they established a dairy. Their home was built by John Weymouth and it still stands on The Knoll Crescent. Frank attended the Coromandel Valley Public School, and as a boy enjoyed roller skating and playing the piano, for which he won several prizes. He also served for a year in the senior cadets. In 1912 he passed the civil service exam and began work as a clerk. Before the war he assisted with gymnasium classes at the Blackwood, Belair and Coromandel Boys’ Club.

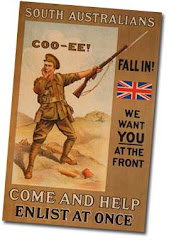

He enlisted on 11 September 1914 at the age of 19, joining 'Cork' Company of the 10th Battalion at Morphettville and boarding the troopship 'Ascanius' on 20 October 1914. By December 1914 the battalion was camped in tents at the foot of the Pyramids in Egypt. Training continued till early April 1915 when the battalion moved to Alexandria and then to the island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea.

About 2pm on the afternoon of 24 April 1915, Frank, loaded down with his pack and rifle, climbed on board the British battleship the 'Prince of Wales', along with the rest of 'Cork' and 'Beer' companies of the 10th Battalion. The 'Prince of Wales' then slipped out of Mudros Harbour, along with other ships carrying the rest of the first wave that was to land on Gallipoli.

Around 7pm that evening the battalion were told they could rest until 11pm. Those that were able to sleep were woken at midnight, and they were all given a welcome cup of hot cocoa by the ships' crew.

At 1am the ships stopped so the soldiers could start climbing down rope ladders into lines of rowing boats moored alongside the battleship. By 2.35am the rowing boats were full, and the battleship set off again with the lines of rowing boats attached to its sides. At 3 am the moon set and the sky grew very dark. At 3.30am the boats cast off from the battleship to be towed in threes towards the distant shore by small steamboats.

It was so dark that they would probably not have been able to see the lines of boats being towed alongside. Perhaps they could have just made out the boat behind or in front. The water was smooth as satin. It was a cool peaceful night. There was still no sign of any sort that the Turks had seen them. Close to the shore, the steamboats cast off the lines of boats, and they began to row.

About 4.29am a figure appeared silhouetted on a cliff overlooking the beach and a shot rang out, whizzed overhead and plunged into the sea. Moments later, as the boats reached the stony beach, Frank and his mates slipped over the side and waded ashore, weighed down by their equipment. Bullets struck sparks off the stones on the beach, and men were killed and wounded in the boats, in the water and on the beach. Those that hadn’t been hit ran across the stony beach to the cover of a sandy bank. They started to scale the steep hill in front of them, some driving their bayonet into the dirt to give them a handhold, as the Turks kept shooting at them with rifles then machine guns, the fire getting heavier and the casualties mounting every minute.

Sometime on that first ANZAC Day, Frank Smith was shot through the left foot. Four agonising days later he finally made it to a hospital in Cairo.

He survived his wound, but it was bad enough that he was repatriated to Australia and discharged as medically unfit in November 1915. He had spent little more than a year in the AIF. His older brother John enlisted a year after Frank, and died of arsenic poisoning whilst training in Egypt in May 1916.

After the war Frank worked on the family farm, eventually taking it over when his father died. He met Muriel Mcintosh at a dance, they married in 1928, and had four children, twins that died shortly after they were born, and Patricia and John. Frank and Muriel were devoted to each other. In 1935, Muriel died when John was only three months old, and it hit Frank very hard. Patricia went to live with her grandparents Jacob and Mary, and John, who was disabled, went to live with an aunt closer to Adelaide. Frank continued to work the dairy farm. Sadly, Frank’s suffering wasn’t over. When John died at the age of twenty two, Frank went down the Sturt River and in his grief dug a dam which today is known as the John Wesley Smith Memorial Lake. It is located within the Frank Smith Reserve, just behind the Coromandel Valley Primary School off Magarey Road. Frank didn’t want the land broken up, so when he sold it to the Mitcham Council he made sure it would be kept as one lot, which is why the community is still able to enjoy it today.

Frank is remembered by his family as a kind man, who played the piano beautifully. He was an active member of the Blackwood RSL. Early in the Second World War he enlisted in the Army for home service, and sometime that year he married Hilda Priest. In 1944 he tried to enlist in the RAAF.

Frank died at the Repatriation Hospital at Daw Park on Ash Wednesday 1983 at the age of 87 and was buried in the Derrick Gardens at Centennial Park. His daughter Pat is still alive, two of his grandsons still live on the Knoll at Coromandel Valley, and his granddaughter Heather works at the Blackwood Library. His name is inscribed on the Blackwood Soldiers' Memorial.

He enlisted on 11 September 1914 at the age of 19, joining 'Cork' Company of the 10th Battalion at Morphettville and boarding the troopship 'Ascanius' on 20 October 1914. By December 1914 the battalion was camped in tents at the foot of the Pyramids in Egypt. Training continued till early April 1915 when the battalion moved to Alexandria and then to the island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea.

About 2pm on the afternoon of 24 April 1915, Frank, loaded down with his pack and rifle, climbed on board the British battleship the 'Prince of Wales', along with the rest of 'Cork' and 'Beer' companies of the 10th Battalion. The 'Prince of Wales' then slipped out of Mudros Harbour, along with other ships carrying the rest of the first wave that was to land on Gallipoli.

Around 7pm that evening the battalion were told they could rest until 11pm. Those that were able to sleep were woken at midnight, and they were all given a welcome cup of hot cocoa by the ships' crew.

At 1am the ships stopped so the soldiers could start climbing down rope ladders into lines of rowing boats moored alongside the battleship. By 2.35am the rowing boats were full, and the battleship set off again with the lines of rowing boats attached to its sides. At 3 am the moon set and the sky grew very dark. At 3.30am the boats cast off from the battleship to be towed in threes towards the distant shore by small steamboats.

It was so dark that they would probably not have been able to see the lines of boats being towed alongside. Perhaps they could have just made out the boat behind or in front. The water was smooth as satin. It was a cool peaceful night. There was still no sign of any sort that the Turks had seen them. Close to the shore, the steamboats cast off the lines of boats, and they began to row.

About 4.29am a figure appeared silhouetted on a cliff overlooking the beach and a shot rang out, whizzed overhead and plunged into the sea. Moments later, as the boats reached the stony beach, Frank and his mates slipped over the side and waded ashore, weighed down by their equipment. Bullets struck sparks off the stones on the beach, and men were killed and wounded in the boats, in the water and on the beach. Those that hadn’t been hit ran across the stony beach to the cover of a sandy bank. They started to scale the steep hill in front of them, some driving their bayonet into the dirt to give them a handhold, as the Turks kept shooting at them with rifles then machine guns, the fire getting heavier and the casualties mounting every minute.

Sometime on that first ANZAC Day, Frank Smith was shot through the left foot. Four agonising days later he finally made it to a hospital in Cairo.

He survived his wound, but it was bad enough that he was repatriated to Australia and discharged as medically unfit in November 1915. He had spent little more than a year in the AIF. His older brother John enlisted a year after Frank, and died of arsenic poisoning whilst training in Egypt in May 1916.

After the war Frank worked on the family farm, eventually taking it over when his father died. He met Muriel Mcintosh at a dance, they married in 1928, and had four children, twins that died shortly after they were born, and Patricia and John. Frank and Muriel were devoted to each other. In 1935, Muriel died when John was only three months old, and it hit Frank very hard. Patricia went to live with her grandparents Jacob and Mary, and John, who was disabled, went to live with an aunt closer to Adelaide. Frank continued to work the dairy farm. Sadly, Frank’s suffering wasn’t over. When John died at the age of twenty two, Frank went down the Sturt River and in his grief dug a dam which today is known as the John Wesley Smith Memorial Lake. It is located within the Frank Smith Reserve, just behind the Coromandel Valley Primary School off Magarey Road. Frank didn’t want the land broken up, so when he sold it to the Mitcham Council he made sure it would be kept as one lot, which is why the community is still able to enjoy it today.

Frank is remembered by his family as a kind man, who played the piano beautifully. He was an active member of the Blackwood RSL. Early in the Second World War he enlisted in the Army for home service, and sometime that year he married Hilda Priest. In 1944 he tried to enlist in the RAAF.

Frank died at the Repatriation Hospital at Daw Park on Ash Wednesday 1983 at the age of 87 and was buried in the Derrick Gardens at Centennial Park. His daughter Pat is still alive, two of his grandsons still live on the Knoll at Coromandel Valley, and his granddaughter Heather works at the Blackwood Library. His name is inscribed on the Blackwood Soldiers' Memorial.